Team Rubric Development

Academic Rubric

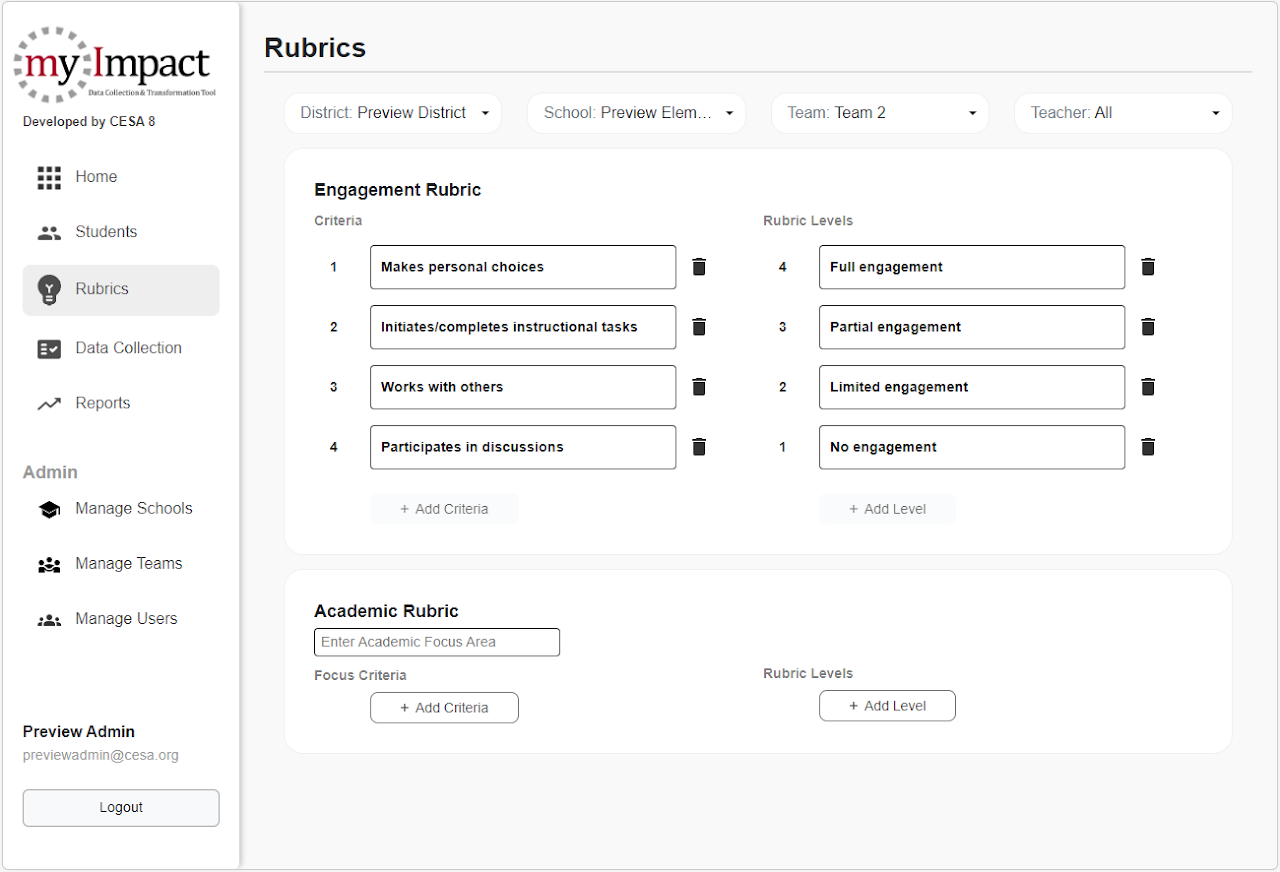

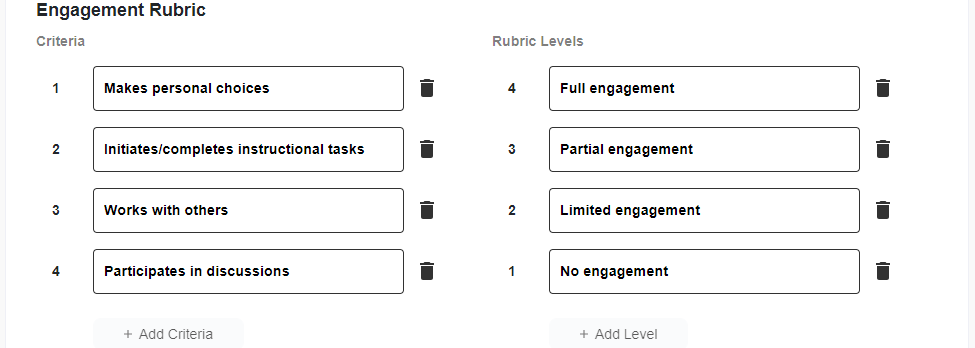

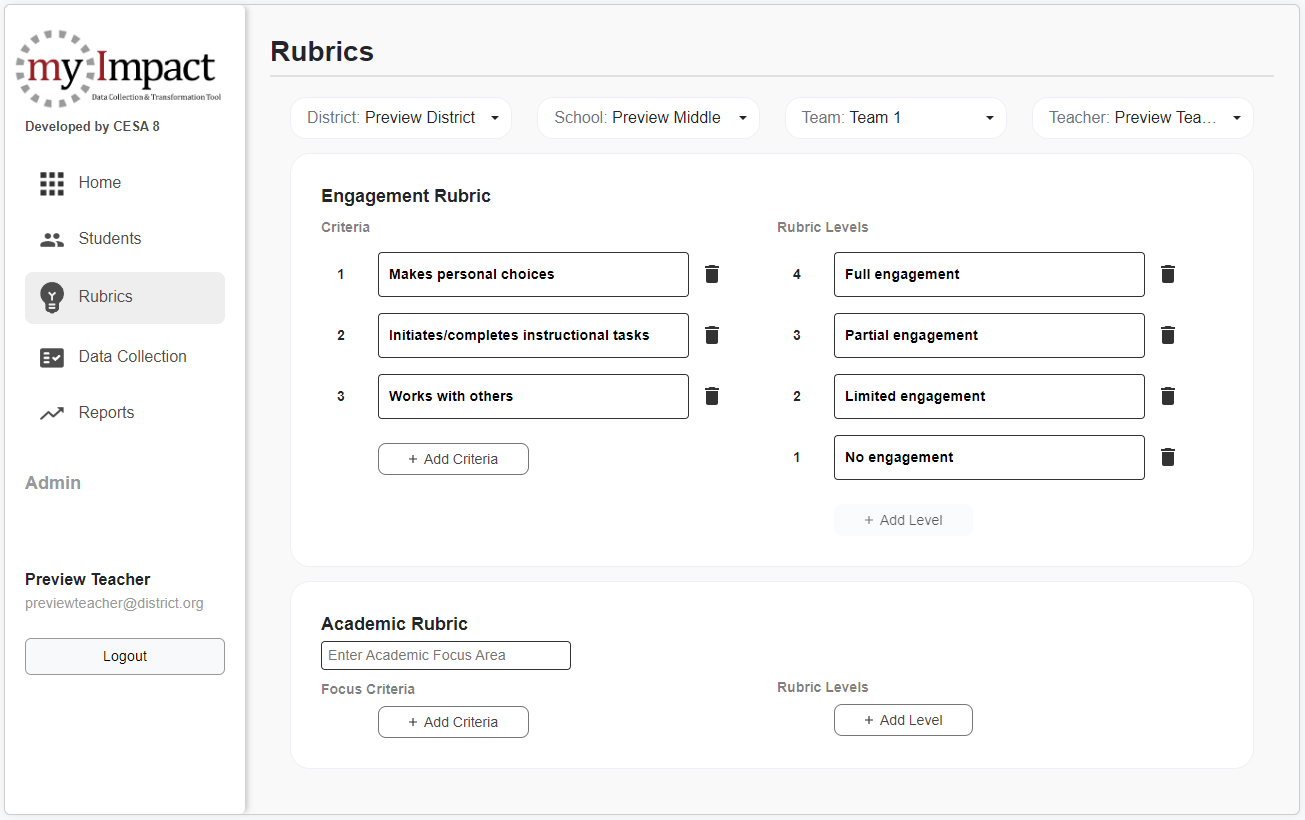

Team Rubric

Rubrics are owned at the team level, not at the teacher-user level. Every teacher on a team has access to the team rubric and can edit the team rubric. Any edit made by one teacher changes the rubric for ALL teachers at any time during the year.

As a team is developing the rubric that will be used for the year, it may be helpful to have only one team member edit the rubric during the discussion.

Academic Focus Area

The Academic Rubric has three parts. The first part is the focus. The focus is an overarching skill, ability, or content big idea that spans an entire year of instruction. The Academic Focus will be used by the team members using myImpact as a centering focus for their discussion of the instructional impact on academics after each strategy trial period. In order for those discussions to be rich and meaningful, all the teachers using the data tool will need to connect to the focus and the criteria in the rubric in a way that is authentic and relevant to their teaching context.

Some examples are Key Ideas and Details for ELA, Makes Sense of Problems and Persevere in Solving Them for math, or Developing and Using Models for science.

Team teachers determine a common academic focus to enter into the "Enter Academic Focus Area" field.

Teachers on the team should choose a focus that builds over an entire year, not a lesson or unit, and has observable criteria in many lessons across the year.

Academic Focus Criteria

The second part of the rubric, Focus Criteria, will contain the observable criteria for the chosen focus. Observable criteria must be measurable, desirable, and likely to change over the course of the year.

Example criteria for the Key Ideas and Details focus area are Makes logical inferences, Cites specific textual evidence, Determines central idea, and Analyzes how individuals interact over the course of a text. Additional examples are found below.

Team teachers identify three to four observable and measurable criteria of the academic focus which are desirable and likely to change over time to enter into Focus Criteria fields added with the +Add Criteria button.

Rubric Level Descriptors

The last section of the Academic Rubric is where the team identifies four rubric level descriptors for their academic rubric criteria to enter into Rubric Levels fields added with the +Add Level button.

The team should decide on a set of descriptors that will be meaningful when capturing observations of student proficiency in the classroom or student work. It is helpful to understand that the descriptors should allow observers to differentiate between multiple degrees of focus area criterion proficiency. To reduce the number of rubric levels, simply click on the trash can next to the level to be removed. The levels will automatically adjust so the scale begins at 1.

Facilitating a Rubric Development Conversation

Why a facilitator?

Having or designating a facilitator during the rubric development discussion enhances the overall quality of the conversation by ensuring balanced participation, creating a safe space, and managing time and progress. Having someone in the facilitator role contributes significantly to fostering effective communication, promoting collaboration, and ultimately achieving consensus among team members when identifying rubric criteria and rubric-level descriptors.

Finding Common Ground for the Academic Focus and Creating Criteria for the Rubric

Scenario 1: All members of the group are similar content and grade band

This scenario is the easiest to find common ground. Narrow the choices of standards to the content area everyone on the team has in common. If you are an elementary group, looking through the ELA anchor standards or math practice standards is a good place to start.

Some questions that may help the team find common ground:

What is an area of constant concern?

When considering testing data, which area could use the greatest improvement?

What essential standards (power standards) are used across the grade levels in this group?

Do you all do writing, research, or presenting in your classes? Perhaps an ELA, social studies or science standard would help find a focus.

Do you do calculating or data analysis in your classes? Perhaps a math or science standard would help find a focus.

If the team chooses a focus area based on a standard, read the descriptors for that standard. Look for phrases that are observable, measurable, and desirable that are likely to change. Think through several units to be certain that the activities and practice students are likely to do will give ample opportunity to gather observational or student work evidence sufficient to allow for assigning rubric scores across the criteria. It is helpful for each teacher to share some ideas of observable or assessable examples for each rubric criterion.

Scenario 2: All members of the group are similar content but different grade bands

This scenario helps members find commonalities across grade levels. Narrow the choices of standards to the content area that all team members have in common. If you are an elementary group, looking through the ELA anchor standards or math practice standards is a good place to start.

To help identify commonalities, first read math practice and/or ELA standards.

Some questions that may help the team find common ground:

Where do you see commonalities across grade levels? What does that look like in higher grade levels? Lower grade levels?

What is an area of constant concern?

When considering testing data, which area could use the greatest improvement?

Are there any essential standards (power standards) used across the grade levels in this group?

Do you all do writing, research, or presenting in your classes? Perhaps an ELA, social studies or science standard would help find a focus.

Do you do calculating or data analysis in your classes? Perhaps a math or science standard would help find a focus.

If the team chooses a focus area based on a standard, read the descriptors for that standard. Look for phrases that are observable, measurable, and desirable that are likely to change. Think through several units to be certain that the activities and practice students are likely to do will give ample opportunity to gather observational or student work evidence sufficient to allow for assigning rubric scores across the criteria. It is helpful for each teacher to share some ideas of observable or assessable examples for each rubric criterion.

Some examples of academic focuses and criteria are located below.

Scenario 3: Members of the group have diverse content and either similar or different grade bands

This scenario requires more discussion than the other two to help team members find commonalities across content areas and potentially grade levels as well. A good place to start is to look through the ELA anchor standards or math practice standards to find one or two examples that might work for everyone present.

Some questions that may help the team find common ground:

Do you all do writing, research, or presenting in your classes? Perhaps an ELA, social studies or science standard would help find a focus.

Do you do calculating or data analysis in your classes? Perhaps a math or science standard would help find a focus.

What is an area of constant concern?

When considering testing data, which area could use the greatest improvement?

If the team chooses a focus area based on a standard, read the descriptors for that standard. Look for phrases that are observable, measurable, and desirable that are likely to change. Think through several units to be certain that the activities and practice students are likely to do will give ample opportunity to gather observational or student work evidence sufficient to allow for assigning rubric scores across the criteria. It is helpful for each teacher to share some ideas of observable or assessable examples for each rubric criterion.

For example, if an art teacher is using the same data tool as a math teacher, having an academic focus of Math Practice 8: Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning (Wisconsin Standards for Mathematics, pg 23) may be a stretch for an art teacher to incorporate in a meaningful way. On the other hand, an art teacher may find Math Practice 7: Look for and make use of structure (Wisconsin Standards for Mathematics, pg 23) applicable because many of the math practice descriptors could be observed as the rubric criteria in the art classroom, i.e. students look closely to discern a pattern or structure, students can recognize the significance of an existing line in a geometric figure, students can shift perspective.

Some examples of academic focuses and criteria are located below.

Examples of Academic Focuses and Criteria

ELA Example (from CCSS ELA Anchor Standards for Reading)

Focus: Key ideas and details

Criteria:

Makes logical inferences

Cites specific textual evidence

Determines central idea

Analyzes how individuals interact over the course of a text

Mathematics Example (from CCSS Math Standards for Mathematical Practice)

Focus: Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them.

Criteria:

Analyzes givens in a problem

Plans a solution pathway

Checks answers

Represents the problem (drawing, objects, or other ways)

Science Example (from NGSS Science and Engineering Practices)

Focus: Developing and using models

Criteria:

Develop a model to represent something in the natural or designed world

Compares models

Revises model during learning

Uses model to test cause and effect relationships

Facilitating Group Discussion: What Do the Engagement and Academic Criteria Look Like in Your Classroom?

Once the team members have decided on the academic criteria, each person should share some concrete examples of what the engagement and academic criteria look like in each teacher’s classroom. Use the following prompts to stimulate thinking and sharing.

Imagine you are planning a unit during a time you will be collecting data on engagement and the academic focus. List the types of activities or work students would have to be doing so you could observe or measure their engagement and the academic criteria.

For one engagement and one academic item on your list, describe to the group what you would look for to give that student a 4, 3, 2, or 1 on the engagement rubric and a 4, 3, 2, or 1 on one of the academic criteria.

Continue around the group until everyone has shared several examples.

You may have questions about the validity of the data and the inter-rater reliability of the scores. Use these answers to come to a common understanding about this issue. In addition, this video, Indicator vs. Measure, can help to differentiate between a measure and an indicator. The data collected for data tool trials are indicators, not measures.

The data tool collects indications we are agreeing represent accurate enough information that can be used with our PROFESSIONAL judgment to determine if the instructional decisions we’ve made have elicited a positive or negative response in student engagement and academics.

We are not collecting standard measurements; we are documenting indications of student response.

We strive to individually collect data in our own classrooms using the same conceptual scale from one data collection event to the next. The precision of having inter-rater reliability to have a discussion of instructional practices isn’t necessary.